Monster on Easthaven beach, 1977

Introduction

East Haven (also: Easthaven) is a fishing village near to the city Carnoustie in the council area of Angus, Scotland, Great Britain. In December 1977 a “monster”, “mystery corpse” or “prehistoric animal” washed up here on the shore, lying in seaweed. Though, the mystery apparently lasted not too long as the same newpaper-article reporting about it revealed the identity as basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus). The history of this little-known case will be examined from several sources like contemporary newspaper-articles and (popular-)scientific literature. The given identity of the creature will be explained from two photography, published in local newspaper Arbroath Guide and literature about “The basking shark in Scotland” from author Denis Fairfax.

History in literature

Fig.1. Cropped picture of the Easthaven monster of December 1977 (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977. Used according to § 51 Urheberrechtsgesetz). See text and Fig. 3, 4 and 5 for detailed anatomical explanation and Fig. 2 for comparision with the shark bycatch at Arbroath. The kneeing man beside it could be photographer David Henderson of Dundee (Anonymous, personal communication, January 9, 2021).

There is seemingly no entry of this case in relevant “sea monster” literature like for example Dinsdale (1966), Heuvelmans (1968) or Newton (2012). Only a short notation can be found in Rosemary Kingsland’s book “Savage Seas”(1998), while introducing the “animal of Stronsa” and the “divided opinion” that it was either unknown or the remains of a basking shark: “After seeing a rotting basking shark in December 1977, which was stranded on the shore of the Tay near Carnoustie, the curator [of Royal Scottish Museum] came to the conclusion that the same description fitted both animals.”

It seems that Kingsland referred to an episode of “Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World” titled “Monsters of the Deep” which was aired on British Television in September 1980. The Curator of Fish, Reptiles and Amphibians of the Royal Scottish Museum’s Department of Natural History, Dr Geoffrey Swinney, presented vertebrae of the Stronsa beast of 1808 and for comparison used three small and two big vertebrae of another individual. He explained: „In the December of 1977 I was fortunate enough in being able to examine a beast which just stranded on the shore of the Tay, near Carnoustie. These are the vertebra of that animal, a basking shark“ (searchfortheunknown. (2009, February 11). Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World: Monsters of the Deep (1980) (Part 3 of 3) [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=XG0V2LZ9fBw. Transcription from Markus Hemmler).

An initial, solitary newspaper-account regarding a “monster” without identification at once – if existing – is missing yet. Summarized, in logical order of events, from various press accounts of December 15 and 16, the story is that “On Monday, a woman walking her dog saw it among seaweed on Easthaven beach and contacted the coastguard.” (‘Monster’ on beach is dead shark, 1977). “’I’ve never seen anything like it in my life!’ That was Carnoustie coastguard William Wolcock’s first reaction to what washed ashore at Easthaven this week. For the first thirty-foot mystery corpse bears little resemblance to any animal living… or dead. ‘It’s pretty rotten and smells very bad,’ reported Mr Wolcock. The carcase is in such bad condition however, that it’s impossible to tell what shape it might once have been.” (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977). “It would appear that the mystery carcase […] is not a prehistoric animal as was at first imagined by Carnoustie Coastguard William Woolcock. One possibility is that it could be the carcase of the 22 foot long basking shark that was found tangled in lobster creels of the Arborath cliffs at the beginning of last month.” (Carcase on beach: shark theory, 1977). “The ‘monster’ washed ashore at Easthaven […] has been identified as the basking shark which was ‘landed’ at Arborath over a month ago and later dumped at sea. This was confirmed yesterday by Angus Environmental Health Officer Mr William Young, Members of the Natural History Department of Dundee Museum and the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh. (“Monster” a shark, 1977). “Mr Young said last night: “It is definitely the same shark and is badly decomposed now. We have been asked by the Natural History Museum in Edinburgh to leave it on the beach until they have a look at it.” (‘Monster’ on beach is dead shark, 1977). “Basking shark carcasses have been the basis of a number of ‘monster’ stories round Scotland’s coasts in the past. So – although dedicated Nessie fans and sea serpent spotters may be reluctant to believe it – that seem to be the explanation. Pity. It would be nice to think there was a chance of spotting sea-serpents in Carnoustie bay. It might do wonders for the tourist trade!” (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977).

In terms of probability and taphonomy it seems possible that both incidents from November at Arbroath and December at Easthaven include the same individual (see Jerlström & Elliot (2005) for taphonomical timeline of a stranded basking shark). However, from the presented data (compared Fig. 1 and 2) a detailed reason for this finding, ruling out the option of a second individual of roughly comparable estimated dimension, remains open. Be that as it may, the newspapers reported:

Fig. 2. Basking shark catch at Arbroath, November 1977 (Monster in his pots, 1977. Courtesy of Christine Baird for National Museums Scotland. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/NMSlibraries/status/1169567377761214464). Compared to Fig. 1 there’s no visual feature to determine if it is the same individual washed up later at East Haven.

“Skipper of the Arbroath fishing boat White Rose, Mr Alex Milne, 32 […], landed an unusually large ‘catch’ yesterday. It was a 22ft. basking shark weighing about 4 ton which had become entangled in the ropes of the boat’s crag and lobster creels, just of the Arbroath cliffs. (Arbroath boat lands 22ft. shark, 1977). Mr Milne reported: “‘The shark had got tangled up in the creels which we laid at the end of last week and had drowned,’ said Alec. ‘It came up surprisingly easily for all its weight, but I lost 20 of my creels.’ Alec and his crew made fast the shark’s carcase alongside the boat and towed it back to Arbroath. A large crowd of onlookers gathered as the shark was lifted on to be taken to a fish meal factory in Aberdeen. (Monster in his pots, 1977). However, the fate of the shark changed as “the basking shark which was brought into Arbroath harbour on Wednesday by the local fishing boat White Rose will not be made into fish meal after all. The fish meal factoray have indicated they are not interested in the 22ft., four ton shark, which became entangled in the ropes of the lobster creels at Arbroath cliffs. Yesterday afternoon the shark was lashed to the side of the boat, taken out to sea and dumped.” (Arbroath shark dumped, 1977).

Photographic evidence

The article of the Arbroath Guide (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977) contained a photography of the carcass in newspaper-quality. Additionally, in Fairfax (1998) a small grayscale-image of cranium and splachnocranium, taken from Mr David Henderson of Dundee (not verified yet, but could be the same name staff member of Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum (Anonymous, personal communication, January 9, 2021)), is published.

The overall scene of Fig. 1 shows a heavily decomposed animal carcass, partially free from tissue, between seaweed on a beach said to be near Easthaven. A kneeing man on its left side allows a rough estimation of its dimensions, which seemingly are in the range from 22 ft (Arborath fishers happy, 1977; Arbroath shark dumped, 1977; Arbroath boat lands 22 ft. shark, 1977) to 30 ft (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977). The picture was taken from the anterior end, the skull is followed from a neck and a bulky middle part with some open visible cartilaginous parts. After it, approximately after two third of the body length, the body bends to the left in a sharp angle of about 80 degree. Posteriorly it tapers to the tail, ending in a triangular form. No other extremities can be acknowledged, also due to the quality of the newspaper-picture.

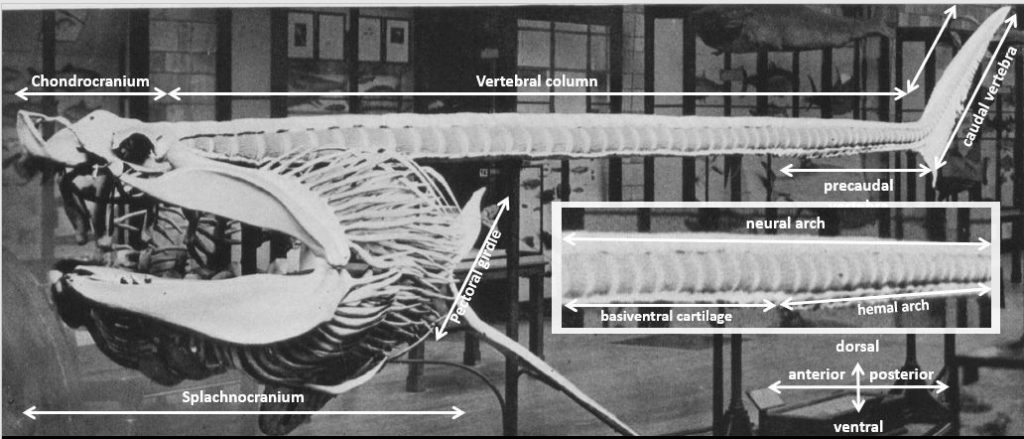

Fig. 3. Wax-model of a basking shark in British Museum with added anatomical terminology used in text (“A Canadian ‘monster’”, 1934. Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library).

The identification as basking shark (C. maximus) can be deduced from both photography. Subsequent anatomical description and terminology of the cartilaginous skeleton is derived from Compagno (1990), Izawa & Shibata (1993), Fairfax (1998), Hamlet (1999), Iuliis & Pulerà (2007) and Klimley (2013) and is visualized in Fig. 3, 4 and 5.

Chondrocranium:

The box-like chondrocranium is fully exposed and viewable from dorsal side, lying slightly lateral on its right side. Certain parts, like all rostral elements (left and right dorsolateral rostral cartilage, median rostral cartilage) or the supraorbital crests (dorsal), are seemingly missing, while the ventral opening of the left nasal capsule and both orbits can be identified. In median line, between the anterior margins of the (seemingly missing) supraorbital crests, the epiphysial foramen, housed in a turret-like rising, is evident. The Henderson photo in opposite to Fig. 1 reveals additionally, that the left supraorbital crest is still attached, but deformed and bending upwards.

Fig. 4. Chondrocranium of the Easthaven monster (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977. Used according to § 51 Urheberrechtsgesetz) and of a basking shark wax-model in British Museum (A Canadian ‘monster’, 1934. Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library) with added anatomical details used in text.

Splachnocranium:

Most parts of the splachnocranium (consisting of the mandibular arch, hyoid arch, gill archs and branchial -rays, etc. pp.) are vanished, in result just leaving the chondrocranium and part of the vertebral column nearly up to the pectoral girdle. This part of the vertebral column, resembling somewhat to a “neck”, in nearly the complete length is still covered largely from tissue. Ventral to the vertebral column a single, larger cartilaginous element remained, what in the close up of Mr Henderson is revealed as element of the mandibular arch (Palatoquadrate or Meckel’s cartilage). Posterior to it three larger cartilaginous elements are viewable, which for the Henderson photo have been identified from Fairfax as “elements of the jaws”, but maybe could also be elements of the gill apparatus instead.

Caudal fin:

It is obvious, that the vertebral column is part of the triangular form at the posterior end of the carcass. In sharks, beginning with the precaudal vertebra, the paired basiventral cartilage below the vertebral centrum form a hemal arch in which the hemal canal provides space for blood vessels from and to the tail. With the caudal fin the neural arches change to epichordal rays while the hemal arch change into elongated hypochordal rays to support the fin. Thus, the triangular form at the posterior end of the Easthaven carcass shows the triangular-shaped upper lobe of the caudal fin consisting of vertebral column, epichordal- and hypochordal rays.

Fig. 5. Splachnocranium and caudal fin of the Easthaven monster (The shark at Easthaven?, 1977. Used according to § 51 Urheberrechtsgesetz) and of a basking shark wax-model in British Museum (A Canadian ‘monster’, 1934. Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library) with added anatomical details used in text.

The presented evidence in summary, especially the anatomy in general, the typical unique taphonomical situation as well as the distinctive features of the cranium, classify the Easthaven carcass definitively as basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Morven Donald, Library and Information Assistant, and Christine Baird at National Museums Scotland, for source material, photographs and helpful information, Emma Longmuir, Museum Assistant at Arbroath Museum, for source material and helpful information too, Scott Mardis for pointing me to the episode of Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World, my anonymous contact helping me with some information regarding Mr Henderson, and Lucinda Moore of the Mary Evans Picture Library for license of The Illustrated London News photograph.

References

A Canadian “monster”: sea cow, basking shark, or “Cadborosaurus”? [Image] (1934, December 15). The Illustrated London News.

Arbroath boat lands 22ft. shark. (November 10, 1977). Aberdeen Press and Journal.

Arborath shark dumped. (November 11, 1977). Aberdeen Press and Journal.

Compagno, L. (1990). Relationships of the megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios (Lamniformes, Megachasmidae), with comments on its feeding habits. In Pratt, H. et al. (Ed.) Elasmobranchs as living resources: advances in the biology, ecology, systematics and the status of the fishery. NOAA Technical Report NMFS 90.

Carcase on beach: shark theory. (December 15, 1977). Courier.

Dinsdale, T. (1966). The Leviathans. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Fairfax, D. (1998). The basking shark in Scotland. East Linton: Tuckwell Press.

Hamlett, William C. ed. (1999). Sharks, Skates, and Rays: the Biology of Elasmobranch fishes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hemmler, M. (2012). ‘Hunda “Scapasaurus” photo (re)discovered, with explanation of descriptive trends in relation to pseudoplesiosaurs.’ The Journal of Cryptozoology 1.

Heuvelmans, B. (1968). In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. New York: Hill and Wang.

Iuliis, G. & Pulerà, D. (2007). The Dissection of Vertebrates: a laboratory manual. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Izawa, K. & Shibata, T. (1993). A young basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus, from Japan. Japanese Journal of Ichthyology, 40 (no. 2): 237-245.

Jerlström, P. & Elliot, B. (2005). A ‘tail’ of many monsters. Technical Journal 19 (2): 74-75.

Klimley, A. (2013). The Biology of Sharks and Rays. London: The University of Chicago Press.

“Monster” a shark. (December 15, 1977). Courier.

Monster in his pots. (November 10, 1977). Courier.

‘Monster’ on beach is dead shark. (December 15, 1977). Aberdeen Press and Journal.

Newton, Michael. (2012). Globsters. Woolserey: CFZ Press.

The shark at Easthaven? (December 16, 1977). Arbroath Guide. In Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.