Gourock sea serpent, 1942

Introduction

The town of Gourock is located on the southwest coast of Scotland, in the upper Firth of Clyde, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean. In close proximity to Gourock, at the anchorage of the Tail of the Bank, the British Home Fleet was stationed during the Second World War. It was during this time, in June 1942, that a purportedly intact „sea monster“ was discovered. Supposedly, due to a lack of interest from scientists and military restrictions on photography, the creature was not thoroughly examined or documented. Only a rough sketch was made by Charles Rankin, the reporting eyewitness and Burgh Surveyor, who also kept a bristle taken from one of its flippers. The remains were subsequently buried beneath the playing field of the present-day local school, St Ninian. It was not until 1980, when Rankin publicly shared his account on a British television series about unexplained phenomena, that the descriptions of the creature sparked various speculations regarding its true nature. In 2012, newspaper articles from 1942 were rediscovered, classifying the creature as a highly decomposed basking shark. Correspondences between Charles Rankin and former curator Dr. A. C. Stephen of the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh were found at the National Museums Scotland Library in 2020. These correspondences provided additional insights into the matter and after thorough evaluation, it becomes evident that the most plausible explanation for the eyewitness account is a combination of genuine and non-genuine observations. As a result, the identification made by the Greenock Telegraph and the Gourock Times holds greater probability in the assessment: the carcass discovered in Gourock in 1942 belonged to a severely decomposed basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus).

History in media and literature

The history of media and literature was divided into several parts: the initial report in the Strathearn Herald and on British Television and the subsequent literature produced from 1980 until the present day, encompassing a range of mediums from books to online-newspapers. The second section presents research findings derived from newspaper articles and postal correspondence exchanged between Rankin and the Royal Scottish Museum. Certain works, which for example may contain only minor data that have already been mentioned elsewhere, will be included solely in the reference list.

Fig. 1. View at McInroy’s Point, Ashton. The sea serpent of Gourock washed up in the vicinity. (Lynn M Reid, 2008. Retrieved from https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/766622. Used under license cc-by-sa/2.0).

The „Gourock Sea Serpent“ gained wider recognition in September 1980 when an episode of „Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World“ titled „Monsters of the Deep“ was broadcasted on British Television. In this episode, the eyewitness Charles Rankin, who in the past served as the Burgh Surveyor and Sanitary Inspector of Gourock, was interviewed. However, the Strathearn Herald also managed to secure an interview with him, and with the permission of the television company, they published an article just two days prior to the documentaries airing:

After the incident of 1942, Rankin relocated to Crieff a few years later, where he once again assumed the position of Burgh Surveyor and Sanitary Inspector for a period of time. Before being contacted by the newspaper, Rankin had kept his encounter with a supposed relative of the Loch Ness Monster almost completely hidden at his new residence. This was due to his conviction that nobody would listen, as had been the circumstance in 1942. Back then in June 1942, he received a report about an unpleasant odor emanating from the vicinity between the town’s built-up area and the Clock Lighthouse. After investigating the matter together with the foreman, as responsible, he “decided to dispose of the carcase before the smell became really offensive and this had to be done before the tide flowed again. There were several reasons why the carcase could not be disposed of by burial on the foreshore and I did not want it to be re-floated and stranded anew at some point near the centre of the town. The carcase was cut up into manageable pieces and removed to the town’s incinerator grounds”. However, prior to proceeding, Rankin contemplated capturing a photograph. But, “during the war years the taking of photographs in this area of the Clyde was prohibited under penalty and although I approached the ‘Wavy Navy’ at their HQ suggesting I might take photographs of the carcase – showing nothing but the foreshore – I was advised that although this type of security was not one of their functions I would be well advised not to be seen taking photographs in that particular area.” He tried to approach the local weekly newspaper, however, the editor showed minimal interest and provided only a brief report in the subsequent issue. In the end, “the remains were buried in the grounds of the town’s incinerator. I had in mind to dig them up at a later date once the flesh had decomposed, but I left Gourock in 1946 and the opportunity was lost.” As Rankin recalled he “read in the ‚Scotsman‘” that pieces of such an animal had been found in Orkneys” [at Deepdale Holm, Mainland], and reached out to the Royal Scottish Museum. They assured that the carcass found in Orkney was that of a basking shark. He remarked that “an illustration of it was sent me and notwithstanding my very full description sent them, I was told that my ‘find’ was also a basking shark.” Rankin also wrote to author Rupert Gould, whom he knew from his appearances discussing sea monsters on children’s radio programs and from whom he read an article entitled ‘Loch Ness Monster is true’. Gould informed him, that “similar carcases had been washed ashore in many parts of the world. – But the animals were ‘something that science would not admit’” (Mystery of a monster is told, 1980).

On September 9, 1942, the documentary „Monsters of the Deep“ was finally aired, featuring the live interview with Rankin:

„I can’t see that this carcass was a rotting basking shark. In the first place this animal showed no signs of rotting. It was absolutely complete. Unmarred. The monster measured approximately 28 feet from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail. The body as it lay on the ground was approximately 5 to 6 feet deep. The body could be described as having three parts – the body, the neck and the tail. And the neck and tail tapered very gradually away from the body. The animal had teeth. Teeth about perhaps that size [Rankin shows the first distal phalanx bone of his left pointer finger] on both jaws. In the stomach of the creature was a small portion of what I took to be a seaman’s jersey. It was an open knitted portion of some knitted material and the other thing strangely enough was the corner of what can be described as an old fashioned tablecloth. Just the corner and it was complete with tassels.“

(searchfortheunknown. (2009, February 11). Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World: Monsters of the Deep (1980) (Part 3 of 3) [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=XG0V2LZ9fBw. Transcription from Markus Hemmler)

In the accompanying book to the Television series the report was more detailed:

“It was approximately 27-28 feet in length and 5-6 feet in depth at the broadest part. As it lay on its side, the body appeared to be oval in section but the angle of the flippers in relation to the body suggested that the body section had been round in life. If so, this would reduce the depth dimension to some extent. The head and neck, the body, and the tail were approximately equal in length, the neck and tail tapering gradually away from the body. There were no fins. The head was comparatively small, of a shape rather like that of a seal, but the snout was much sharper and the top of the head flatter. The jaws came together one over the other and there appeared to be a bump over the eyes – say prominent eyebrows. There were large pointed teeth in each jaw. The eyes were comparatively large, rather like those of a seal but more to the side of the head.

The tail was rectangular in shape as it lay – it appeared to have been vertical in life. Showing through the thin skin there were parallel rows of ‘bones’ which had a gristly, glossy, opaque appearance. I had the impression that these ‘bones’ had opened out fan-wise under the thin membrane to form a very effective tail. The tail appeared to be equal in size above and below centre line.

At the front of the body there was a pair of ‘L’-shaped flippers and at the back a similar pair, shorter but broader. Each terminated in a ‘bony’ structure similar to the tail and no doubt was also capable of being opened out in the same way.

The body had over it at fairly close intervals, pointing towards, hard, bristly ‘hairs’. These were set closer together towards the tail and at the back edge of the flippers. I pulled out one of these bristles from a flipper. It was about 6 inches long and was tapered and pointed at each end like a steel knitting needle and rather of the thickness of a needle of that size, but slightly more flexible. I kept the bristle in the drawer of my office desk and sometime later I found that it had dried up in the shape of a coiled spring.

The skin of the animal was smooth and when cut was found to be comparatively thin but tough. There appeared to be no bones other than a spinal column. The flesh was uniformly deep pink in colour, was blubbery and difficult to cut or chop. It did not bleed, and it behaved like a thick table jelly under pressure. In what I took to be the stomach of the animal was found a small piece of knitted woolen material as from a cardigan and, stranger still, a small corner of what had been a woven cotton tablecloth – complete with tassels.”

Neither Rankin nor his foreman, who also inspected the remains, could decide what species this carcass was. Rankin recalls that he rang the Royal Scottish Museum but they dismissed it without interest. Due to war time restrictions he was refused by the Royal Navy with a stiff warning to take any photographs of the carcass. So the carcass at last was hacked into pieces and buried in the grounds of the municipal incinerator, what today is the playing field of local school St Ninian (Welfare & Fairley, 1980).

Author Paul Harrison (2001) argued that if the description was accurate, it could not relate to a decomposed basking shark and instead sounds more like a species of pinniped. Therefore, he remained inconclusive especially as Rankin seemed experienced with seals to him.

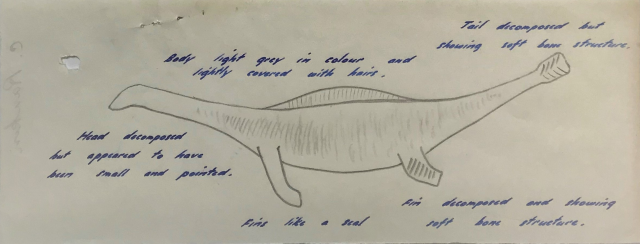

Fig. 2. Original sketch drawn from Charles Rankin of the Gourock carcass. Attached to a letter to Dr Stephen and later shown during a interview for “Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World”. (Courtesy of Christine Baird for National Museums Scotland. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/NMSlibraries/status/1200385620540981248).

Zoologist Dr Karl P. N. Shuker (1995a, 1995b, 2003, 2012) more conclusively wrote that “when considered collectively, features such these bristles (readily recalling the ceratotrichia – cartilaginous fibres – of a shark fin rays), the lizard-like shape, vertical tail (characteristic of fish), lack of body bones, and smooth skin suggest a decomposing shark as a plausible identity (i.e. adopting the deciptive ‘pseudoplesiosaur’ form so frequently reported for rotting basking sharks)”. The problem with this explanation appears to Dr Shuker that, if the report was accurate, the description of large pointed teeth argues against such an identity and instead favors a carnivorous species. Noting also that, if this would be true, it has to be a very large carnivorous shark as even the largest carnivorous shark, the great white shark Carcharodon carcharias, rarely exceeds 20 feet.

Newton (2012) dismissed the possibility of the creature being a basking shark due to the reported presence of prominent teeth, and ruled out a carnivorous shark based on the animals reported size. However, he astutely recognized that the absence of bones eliminated the possibility of the creature being a bony fish, reptile, or mammal.

Furthermore, Glen Vaudrey (2012) referenced the case and, given that Rankin seemed to be the only available source at that time, speculated about the possibility of it being a hoax (Glen Vaudrey, personal communication, August 30, 2012).

In 2023, Christopher McEleny, a Scottish politician, submitted a Freedom of Information (FOI) request to Inverclyde Council regarding Rankin and the incident. The acceptance status of the request remains uncertain as an official response has not yet been made accessible to the public. Anyway, according to press, a spokesperson for the council acknowledged Charles Rankin as the Burgh Surveyor and that he had claimed to have discovered a sea creature washed up at shore. The spokesperson also reiterated well-known details regarding the prevention of photography, as well as the incineration and burial processes. In addition to this, the Public Protection Service’s Contaminated Land Officer has assessed it unlikely, that much identifiable material remains following the incineration process. Even as “there are references to the monster being cut up and buried”, “depending on ground conditions it is unlikely there would be much tissue remnants after 81 years of decomposition.” McEleny believes that “we might never know what this sea monster was but from contemporary drawings by the town clerk of the time it looks strikingly like historical descriptions of the Loch Ness Monster”. (Bloke claims he chopped up and incinerated Loch Ness Monster’s stinking rotting carcass, 2023).

History of 1942

Research conducted by Hemmler (2012) resulted in a collection of articles published in local newspapers during the year 1942. The Greenock Telegraph reported on 10th June:

“Gourock workmen have had many novel jobs encrusted to them since the outbreak of war. But to-day they had a task which must be the most unique given to them so far.

They cremated and then buried the remains of a basking shark washed up on the beach at Ashton. The fish was twenty-seven feet in length. It was in such a state of decomposition that no dealers could be prevailed upon accept custody of the “body,” with the result that workmen yesterday set about cutting it into pieces, and removing it to the destructor ”(Away with the body!, 1942).

On June 12th, two days after the Greenock Telegraph, the Gourock Times also published a report:

“Gourock burgh employees have tackled many novel jobs in recent years, but this week they had a task to perform which must be the most unique given them so far. A basking shark, twenty seven feet in length, was washed up on the shore near M’Inroy’s Point. It was in such a state of decomposition that no dealers could be prevailed upon to accept custody of the “body.” Workmen had to set about cutting it into pieces and removing it to the destructor, where it was cremated and the remains then buried” (Notes and Notices, 1942).

Of special interest is the statement in a short notice of the Gourock Times on June 11, 1942, that in contrary to what was known until then there was an expert identifying the carcass: “Gourock’s monster washed up on the beach at the beginning of the week was the subject of argument. It needed an expert to come in and prove that it was a basking shark” (Variorum, 1942).

It appears that the aforementioned expert was not from Edinburgh. The Library of National Museums Scotland has preserved a collection of letters assembled by Dr. A. C. Stephen, who served as the Keeper of the Natural History department at the Edinburgh Museum. The correspondence between the eyewitness, Rankin, and Dr. Stephen commenced on June 13, 1942.

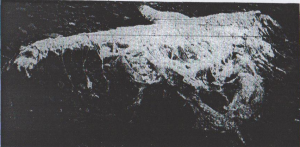

Fig. 3. The Deepdale Holm carcass found at Mainland, Orkney Islands. Charles Rankin thought it was confirmed as basking shark and then reported about a “similar” carcass washed ashore in Gourock. (From “Basking shark or “Scapasaurus”?”, 1942. The Orkney Blast. Used according to § 51 Urheberrechtsgesetz).

The Burgh Surveyor referred to the Deepdale Holm case of February 1942, which he thinks was confirmed as basking shark, and reported about a “similar” carcass at Gourock which due to the “proximity to a public roadway” and “its advanced state of decomposition” was removed as soon as possible:

The body was long – about 5’0” deep over a dorsal fin – tapering gradually to a long neck and long tail. The head was small and the tail fin was flat, soft, bony structure. The total length of the animal was approximately 27’-0””, the fore-part of the body carried two seal-like fins, while behind these were two shorter and wider fins of the same soft bony structure as the tail. The body was light grey in colour, and appeared to have been lightly covered with bristly hairs. The body appeared to have had no bones other than hollow spinal column and the flesh was pink in colour and like fat in appearance. Incidentally, in the belly of the animal was found a green woolen pull-over and a woven cotton article like a bed or table-cover” (Rankin, 1942a).

Dr Stephen (1942a) acknowledged the identification of the Deepdale Holm carcass and answered with several general facts about basking sharks. Lastly, he stated that “from your description the animal washed ashore at Gourock was evidently a Basking Shark, but in a very advanced state of decomposition. This is shown by the short bristly “hairs” which are the frayed ends of the muscle-fibres”.

But Rankin (1942b) rejected such an identification and enclosed the sketch of the carcass, which was shown also later during his interview for Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World in 1980, stating that he is “quite convinced that the body washed ashore here was not that of a basking shark”.

Cautious Dr Stephen (1942b) remarked that “without having seen the animal, it is, of course, impossible to be absolutely certain, but from your very accurate sketch and your description I still think it is a Basking Shark”. He described the taphonomical processes, which led to the appearance of a “sea monster” and enclosed newspaper-cuttings of the Deepdale Holm-case as example.

Rankin (1942c) answered: “The photograph [of the Deepdale Holm-shark] resembles closely the body washed ashore in Gourock but our one was not nearly so decomposed and the long neck and body was complete with the skin practically unbroken, and the teeth in the head were large and in a single row, unlike the rows of thin sharp teeth of a shark. The head was certainly about the size of that of a cow and there were two knobs or bumps on the top”. Rankin within this letter attached a “hair”, “pointed at both ends” and “resembling a steel knitting wire in shape”, which he pulled from one of the back fins. Again, he stated he is “convinced that the animal was not decomposed from the outline of the sketch of the basking shark which you sent me”.

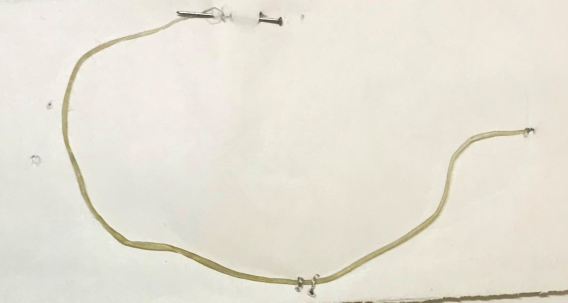

Fig. 4. „Hair“ or „Bristle“ which was pulled out from a flipper of the Gourock carcass. About 6 inches long, tapered and pointed at each end. (Courtesy of Christine Baird for National Museums Scotland. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/NMSlibraries/status/1200385620540981248).

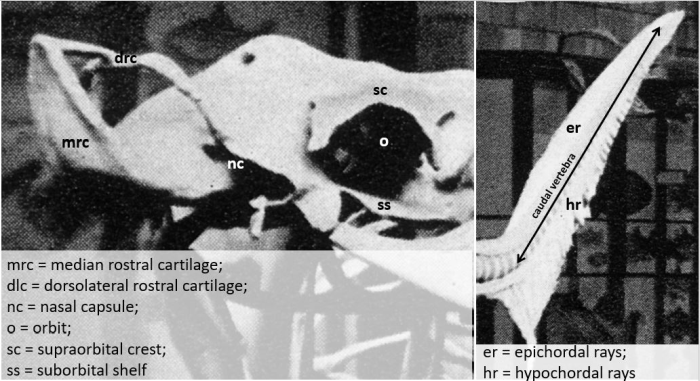

Dr. Stephen (1942c) responded by stating that the „hair“ is indeed „of the type, called dermal rays which make up part of a shark fin” while the description of the teeth would exclude a basking shark. Therefore, he suggested recovering the remains in a few months to secure the skull and teeth, which Rankin (1942d) acknowledged doing within a month or two. However, in 1977, he responded to an inquiry from Dr. Swinney, the Curator of Fish, Reptiles, and Amphibians at the Royal Scottish Museum, stating that he had left Gourock in 1946 and therefore did not have the opportunity to excavate the remains (Rankin, 1977). He presented a sketch intended to depict the location where the carcass was buried. However, the sketch actually portrays a very broad area encompassing Kirn Drive, Georg Street, Larkfield Road, Gourock Castle, Drumshantie Road, and Staffa Street. This encompasses the St. Ninian football field, as well as various other locations, what actually seems to be unhelpful for the intended purpose.

Examination of a story

Rankin stated that he remembered upon an article in The Scotsman discussing the Deepdale Holm carcass (Mystery of a monster is told, 1980). This particular topic has been covered by the newspaper four times, starting with brief descriptions („Carcase of ‚Monster'“, 1942), and then progressing to more detailed accounts including the identification as basking shark. Thus, „Orkney monster“ (1942) not only featured a sketch but also mentioned the initial belief that it could be a plesiosaur while „Orkney Monster Carcase“ (1942) included the same photograph of the Deepdale Holm carcass, which was later in 1942 sent to Rankin by Dr. Stephen (1942b). Hence, it appears plausible that he possessed knowledge regarding crucial aspects of the customary narrative associated with such cases prior to his contact with the museum. However, the specific article that Rankin read and its impact on his statements remain unresolved. Certain is that Rankin was aware of the identification as basking shark. In light of this, he emphasized the resemblance between the Gourock and the Deepdale Holm carcasses. Therefore, it would have been reasonable to expect the same identification. However, instead, the eyewitness rejected this identification immediately following Dr. Stephens‘ response.

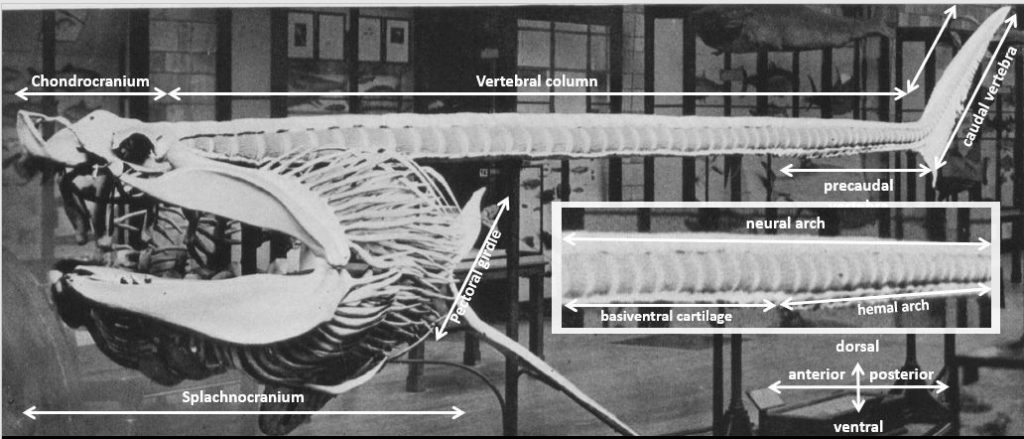

Undoubtedly, the description and sketch bore a superficial resemblance to a plesiosaur, which is an extinct order or clade of marine reptiles. Almost since their classification as a group and new genus in the 19th century (De la Beche, H., & Conybeare, W., 1821), the possibility of the survival of plesiosaurs has been a subject of interest. This has led to the identification of „the“ plesiosaur as a potential sea and lake monster worldwide, including the Deepdale Holm carcass (Carcase of “Monster”, 1942; Orkney monster, 1942; Fresh light on the myster of the Holm shore “Monster”, 1942; Land, sea and Loch monsters, 1942; Basking shark or “Scapasaurus”?; Naval author on the “Monster”, 1942). However, contrary to the survival of an extinct group of marine reptiles, a possible identification as decomposed basking shark can be deduced from numerous instances of what is known as „pseudo-plesiosaur.” This term, seemingly coined or first used in print by Dr Heuvelmans in 1965, refers to stranded marine animal carcasses that bear a superficial resemblance to plesiosaurs (characterized by a small head, long neck, four fins, and a tapering tail), but are ultimately revealed to be heavily decayed basking sharks (e.g. Stronsa 1808, Querqueville 1934, Deepdale Holm 1941/42, Girvan 1953). The specific taphonomic circumstances that have resulted in such an appearance are frequently explained in the sources of these cases, as well as in various books (e.g. Norman & Fraser, 1938; Heuvelmans, 1965;, Shuker, 1995b). Notably also from Gould (Naval author on the “monster”, 1942; Dinsdale, 1966) and thus, it seems worth to question the exact context of the citation in the Strathearn Herald (Mystery of a monster is told, 1980). The following anatomical description and terminology of the cartilaginous skeleton w derived from Compagno (1990), Izawa & Shibata (1993), Fairfax (1998), Hamlet (1999), Iuliis & Pulerà (2007) and Klimley (2013).

Fig. 5. Wax-model of a basking shark in British Museum with added anatomical terminology used in text (“A Canadian ‘monster’”, 1934. Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library).

It is commonly observed that many components of the shark’s splachnocranium, such as the mandibular arch, hyoid arch, branchial arches, and -rays, have either vanished or, at the very least, shifted from their original anatomical positions. As a result, only the small chondrocranium and the vertebral column, which gradually narrows from the pectoral girdle, remain intact. This explains the „small head“ and „neck that taper from the body“, as reported by Rankin (1942a; Welfare & Fairley, 1980). The presence of two knobs or bumps located „on top of the head“ (Rankin, 1942c) may indicate the remnants of the left and right dorsolateral rostral cartilage, positioned in front of the nasal capsules. However, this description leaves also the option that these structures can be described as the „bump over the eyes – say prominent eyebrows“ (Welfare & Fairley, 1980), which can be identified as supraorbital shelves of the chondrocranium.

The phrase „no bones other than spinal column“ (Rankin, 1942a) indicates the absence of any additional skeletal components, such as ribs, limb girdles, or limbs, that are composed of bone. However, some „‘bones‘“ are mentioned in relation to the tail and the four flippers (Welfare & Fairley, 1980). This differentiation refers to distinct components within the skeletal structure. In the case of sharks, their skeletal structure is composed of cartilage, which gives their tail and fins a „gristly, glossy, and opaque appearance“, as described in the Gourock carcass. The vertebral column may appear more „bony“ due to its presence, consistency, and calcification.

The “tail [which] tapered very gradually away from the body” matches a heterocercal caudal fin, where the vertebrae extend into the upper lobe. The lower lobe, composed of thin and flexible horny fin rays called ceratotrichia, either disappears or is no longer recognized as a distinct lobe due to decomposition. The “parallel rows of ‘bones’” with the “impression opened out fan-wise under thin membrane” refer to elongated hypochordal rays which support the caudal fin. The “bony structure similar to the tail” of front and back “flippers” is the somewhat similar appearing radial cartilage of fins. Following, “at back edge of flippers”, are again ceratotrichia which are compared as “hard, bristly ‘hair’” which is “6 inches long, tapered and pointed at each end like steel knitting needle”.

Fig. 6. Cranium and dorsal fin of a basking shark in detail. Wax-model in British Museum with added anatomical terminology used in text (“A Canadian ‘monster’”, 1934. Courtesy of the Mary Evans Picture Library).

In summary, the discovery of a pseudo-plesiosaur offers a credible explanation for those anatomical descriptions, which can be discerned from the subjective information provided by the eyewitness. However, there seem to be two problematic issues associated with such an identification that require consideration. Moreover, there is an additional issue within the stories anatomical description that is inherently problematic. Specifically, the uncertainties surrounding the precise level of decomposition, the reported absence of almost all bony skeletal elements, and the presence of large pointed teeth.

In terms of the level of decomposition, Rankin (1942a) initially described it as being in an „advanced state of decomposition“, which was also reported by the press (Away with the body!, 1942; Notes and Notices, 1942). However, later Rankin mentioned that it was „not nearly so decomposed“ (1942c). This limited decomposition is seemingly backed by the explanatory texts that accompany his sketch, which solely mention the disintegration of the head, fins, and tail. Ultimately, it “showed no signs of rotting. It was absolutely complete. Unmarred” (Welfare & Fairley, 1980). Thus, the description has undergone a significant change following the possible identification as a decomposed basking shark from Dr Stephen. Although a fallible memory of Rankin in 1980 could have been a factor, the level of otherwise detailed remembrance was remarkably high, and there is clear support for a decomposition from the sketch and texts he showed during the interview. Therefore, it seems unlikely that a significant and noteworthy detail such as an „advanced state of decomposition“ would have been subject to memory errors.

The second concern revolves around the observation that „the body seemed to lack any bones except for a hollow spinal column.“ (Rankin, 1942a). This absence is highly unlikely for a marine creature, known to possess a bony skeletal structure, which was recently alive and has not undergone decomposition, as claimed. As a result, this exclusion effectively eliminates the possibility of considering extinct marine reptiles, such as the plesiosaur. Moreover, it is logical to rule out any surviving prehistoric marine reptiles, Osteichthyes, Cetacea, and similar species with a bony skeleton as potential explanations. Hence, the most reasonable conclusion to derive from this objection is that the identity in question relates to an animal distinguished by a cartilaginous skeleton, such as a shark.

Fig. 7. Section of a basking shark jaw featuring multiple rows of teeth. Image: Hannah Keogh (2011). Creative Commons License BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The aforementioned observations cast significant doubt on the accuracy of the report. Though, it seems reasonable to consider a carnivorous shark species given the description of large, pointed teeth as like other filter-feeding sharks, basking sharks possess very small teeth, only a few millimeters in height (Kunzli, 1988; Welton, 2015). The term „large“ in context to the Gourock animal refers specifically to the size of the distal phalanx bone in the left pointer finger, as shown by the eyewitness. (Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World: Monsters of the Deep (1980)). When comparing the dentitions of great white sharks of varying sizes (Shimada, 2002), it can be deducted that the so-called „large“ tooth has actually to be a smaller lateral, rather than a larger anterior tooth. Regardless of the question of why Rankin chose a small tooth instead of a more impressive one, as he (1942c) explicitly rejected a shark identity based on the presence of only one-rowed teeth (shark teeth are in a constant state of shedding and replacement, with new teeth growing in several visible rows behind them), it is also not feasible to consider a carnivorous species of shark as a viable option at all.

After conducting a thorough analysis of basking shark anatomy and taphonomy, including the provided sample in the form of a ceratotrichia, it becomes clear that the majority of these findings support a positive explanation of such an identification. Furthermore, after careful examination of the objections to the eyewitness report and their implications on the overall coherence of the story, it becomes evident that the most plausible explanation for Charles Rankin’s account is, unfortunately, a combination of both genuine and non-genuine observations. Therefore, for this case it is worth reiterating the recognition of the Greenock Telegraph and the Gourock Times in this matter. The remains discovered in Gourock in 1942 were identified as those of a severely decomposed basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus).

Based on this positive identification, it lastly is highly likely that even if Rankin indeed had been willing to excavate parts of the shark that managed to survive the incineration, it would have primarily been components capable of withstanding decomposition, such as the vertebral column or teeth, rather than the cranium. Ultimately, both the vertebral column and especially teeth would have contributed equally to the identification of the species as basking shark.

Acknowledgements

My deepest thanks to Dr Karl Shuker, Glen Vaudrey, Claire Jaycock, Scott Mardis, Richard Freeman and especially to Betty Hendry, Senior Library Assistant at Watt Library, Morven Donald, Library and Information Assistant at National Museums Scotland and Sarah McLean from the Orkney Library and Archive .

References

A Canadian ‘monster’. (1934). [Photo]. The Illustrated London News.

Away with the body! (1942, June 10). Greenock Telegraph.

Basking shark or “Scapasaurus”? (1942, February 6). The Orkney Blast.

Boyle, F., & Cailler, A. (2023, October 26). Man claims he chopped up and incinerated Loch Ness

Monster’s carcass. Irish Star. https://www.irishstar.com/news/ireland-news/man-claims-chopped-up-loch-31287147

Cailler, A. (2023, October 22). Bloke claims he chopped up and incinerated Loch Ness Monster’s stinking rotting carcass. https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/weird-news/bloke-claims-chopped-up-incinerated-31227110

Carcase of “monster”. (1942, January 26). The Scotsman.

Charles, D. (2023, October 23). Man Claims He Found And Buried The Loch Ness Monster In 1942 And The Royal Navy Covered It Up. BroBible. https://brobible.com/culture/article/man-claims-found-buried-loch-ness-monster-1942/

Christine Baird. (2019a). ‘Hair’ or ‘Bristle’ which was pulled out from a flipper of the Gourock carcass. About 6 inches long, tapered and pointed at each end. [Photo]. National Museums Scotland. https://twitter.com/NMSlibraries/status/1200385620540981248

Christine Baird. (2019b). Original sketch drawn from Charles Rankin of the Gourock carcass. Attached to a letter to Dr Stephen and later shown during a interview for “Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World”. [Photo]. National Museums Scotland. https://twitter.com/NMSlibraries/status/1200385620540981248

Compagno, L. (1990). Relationships of the megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios (Lamniformes: Megachasmidae), with comments on its feeding habits. NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS, 90, 357–379.

De Iuliis, G., & Pulerà, D. (2007). The dissection of vertebrates: A laboratory manual. Elsevier/Academic Press.

De la Beche, H. T., & Conybeare, W. D. (1821). Notice of the discovery of a new Fossil Animal, forming a link between the Ichthyosaurus and Crocodile, together with general remarks on the Osteology of the Ichthyosaurus. Transactions of the Geological Society of London, 5(1), 559–594.

Deepdale monster. (1942, February 12). The Scotsman.

Dinsdale, T. (1966). The Leviathans. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Fairfax, D. (1998). The basking shark in Scotland: Natural history, fishery and conservation. Dundurn.

Fresh light on the mystery of the Holm shore ‘monster’. (1942, February 5). The Orcadian.

Hamlett, W. C. (Ed.). (1999). Sharks, skates, and rays: The biology of elasmobranch fishes. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hannah Keogh. (2011). Section of a basking shark jaw featuring multiple rows of teeth. [Photo]. https://www.flickr.com/photos/hannahbanana/

Harrison, P. (2001). Sea serpents and lake monsters of the British Isles. Robert Hale.

Heuvelmans, Bernard. (1965). Le Grand Serpent de Mer. Plon.

Izawa, K. & Shibata, T. (1993). A young basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus, from Japan. Japanese Journal of Ichthyology, 40(2).

Klimley, A. P. (2013). The biology of sharks and rays. The University of Chicago Press.

Kunzlik, P.A. (1988). The basking shark. Scottish Fisheries Information Pamphlet, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland, 14.

Land, sea and Loch monsters. (1942, February 6). Press and Journal.

Lynn M Reid. (2008). View at McInroy’s Point, Ashton. The sea serpent of Gourock washed up in the vicinity. [Photo]. 15 April, 2008

Man claims he found the Loch Ness Monster and buried it beneath a school. (2023, October 22). LADbible. https://www.ladbible.com/news/uk-news/man-claims-he-found-the-loch-ness-monster-and-buried-it-under-school-173447-20231022

Mystery of a monster is told. (1980, September 6). Strathearn Herald.

Nature Notes of the Week. (1942, February 19). The Orcadian.

Naval author on the “monster”. (1942, February 26). The Orcadian.

Newton, M. (2012). Globsters. CFZ Press.

Norman, J. & Fraser, F. (1938). Giant fishes, whales and dolphins. W. W. Norton & Company.

Notes and Notices. (1942, June 12). The Orcadian.

Orkney monster. (1942, January 30). The Scotsman.

Orkney monster carcase. (1942, January 31). The Scotsman.

Rankin, Charles. (1942a, June 13). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Rankin, Charles. (1942b, June 16). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Rankin, Charles. (1942c, June 30). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Rankin, Charles. (1942d, July 3). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Rankin, Charles. (1977, July 11). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Roesch, Ben. (2007). A lesson about tusked sea-serpent carcasses. http://www.forteantimes.com/exclusive/roesch_01.shtml

Shimada, K. (2002). The Relationship between the Tooth Size and Total Body Length in the White Shark, Carcharodon carcharias (Lamniformes: Lamnidae). Journal of Fossil Research, 35.

Shuker, K. P. N. (1995). In search of prehistoric survivors: Do giant ‘extinct’ creatures still exist? Blandford.

Shuker, K. P. N. (2003). The beasts that hide from man: Seeking the world’s last undiscovered animals. ParaView Press.

Shuker, K. P. N. (2012, December 15). ShukerNature: THE GOUROCK SEA SERPENT – METAPHORICALLY EXHUMING A LONG-BURIED CRYPTO-MYSTERY. ShukerNature. https://karlshuker.blogspot.com/2012/12/the-gourock-sea-serpent-metaphorically.html

Shuker, Karl P. N. (1995). Bring Me the Head of the Sea Serpent! Strange Magazine, 15. http://strangemag.com/seaserpcarcsshuk.html#TheGourockCarcass

Stephen, A. (1942a, June 15). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Stephen, A. (1942b, July 2). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Stephen, A. (n. d.). [Gourock animal]. Letters about alleged Monsters July 1934 – August 1950. National Museums Scotland.

Variourum. (1942, June 11). The Gourock Times.

Vaudrey, G. (2012). Sea serpent carcasses: Scotland: From the Stronsa monster to Loch Ness. CFZ.

Welfare, S., Fairley, J., & Clarke, A. C. (1980). Arthur C. Clarke’s mysterious world. Fontana/Collins.

Welton, B. J., 2015, A new species of Late Early Miocene Cetorhinus (Lamniformes: Cetorhinidae) from the Astoria Formation of Oregon, and coeval Cetorhinus from Washington and California. Contributions in Science, 523, p. 67-89. Contributions in Science.

Article revised and updated: 25.04.2024