The sea serpent dragon’s head of Ningpo, 1905

Introduction

In 1905 the head of a supposed “sea serpent” was brought to Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. William Herbert Melton Ayres originally bought it from a fisherman of Ningpo, China, and related it to the legendary dragons of China. Speculations about its true nature so far ranged from dragon or descendant of a prehistoric marine reptile to toothed whale. Its history will be examined from newspaper-articles, while its identity will be explained from a published photography for the first time since 1905.

Literature

Fig. 1. Sketch of a Chinese dragon. (Flag of the Qing Dynasty (1889-1912).svg. (2018). Wikimedia Commons. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_Qing_Dynasty_(1889-1912).svg. Used under license CC BY-SA 4.0)

The first mention of this case in “sea monster” literature had author Richard Muirhead (2014), while the blog-article includes merely a full citation of the story published from the Jonesboro Evening Sun of May 11, 1905. As often the referred newspaper-text is generic and was published in several newspapers across the USA:

“Model of China’s Dragon

Head of sea serpent recently captured displayed in Honolulu.

Honolulu is the possessor of the head of a real sea serpent. The intact bones of the curious head are on exhibition in the window of a store in that city, and hundreds of curious people crowd around the place waiting in line to get a glimpse of the strange object, says a recent report to the New York Sun. William Herbert Melton Ayres brought to Hawaii what is probably the first head of a sea serpent to be placed on exhibition. He came to Hawaii seven years ago, later went to Shanghai and a short time ago he returned to Honolulu quite unexpectedly. He walked into the office of the Bulletin and asked if that paper cared to have a story about a sea serpent. He was asked not to slam the door in going out. Nothing daunted, Ayres again descended upon the office, bearing a large carpet bag. Depositing the package on the sporting editor’s desk he insisted upon opening it, and revealed to the surprised gaze of all the bones of the head of a huge sea monster. The jawbones measured about four feet, the head being a couple of feet wide. There were 160 teeth, 80 upper and as many lower. The specimen was utterly unlike anything seen as far as the records go. Ayres stated that he had purchased the head from a Chinese fisherman who had found the body of the serpent washed upon the shore, the body measuring 78 feet, apparently having been killed by some passing steamer. Ayres believes that the serpent thus discovered is a descendant of the monster which inspired the dragon upon the flag of China.” (“Model of China’s dragon”, 1905a; 1905b; 1905c; 1905d; 1905e; 1905f; 1906; “Model for China’s dragon”, 1905)

In context to reports about surviving prehistoric animals author Dr Karl Shuker (2016), without giving a positive identification due to the lack of solid evidence, categorized it as “a specimen of the marine saurian category [a speculative construct in cryptozoology to anatomically arrange similiar reports of „sea monster“], but its head was actually on public display for a time […]” and added that “of course it is possible that the specimen was merely a toothed whale (odontocete) skull […]”. Without any further data a reasonable explanation for the reported length, even if (slightly) outside the maximal range of the largest toothed whale species, the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus). But this suggestion would be inconsistent in relation to the given measurements of the head and high number of teeth as generally only smaller Odontocete, like for example members of the family of Delphinidae, possess such great numbers.

The length and those other described features of the body in opposite to the head are based on verbal report and not on personal examination through Ayers as will become clear from an inside report of the local newspaper The Pacific Commercial Advertiser:

“Marine snake head from China

Through the courtesy of Mr. H. Melton Ayres, who returned from China last week, we are enabled to publish photographs of what Mr. Ayres thinks is the only sea serpent’s head in existence.

Since the first newspaper was published the more or less fabled doings of the great marine snake have been intermittently chronicled the world over, but until now these stories have lacked woefully in substantiation.

Now comes Ayres out of the East with not only the life story of the snake but armed with the head of the serpent itself.

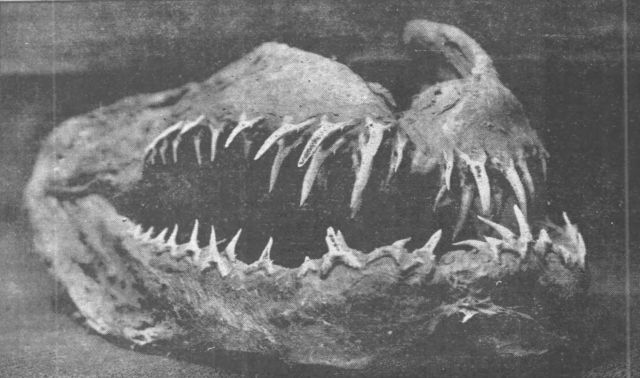

Fig. 2. Sea serpent dragon “head” of Ningpo, China. (From “Marine snake head from China”, 1905. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Used according to § 51 Urheberrechtsgesetz).

The reptile came ashore in an injured condition near Ningpo last October and was quickly despatched by the populace who feasted on the body and impaled the head on a pole.

Ayres learned of the affair from a Chinaman in his employ and immediately took steps to secure what was left of the skeleton. He was only able to obtain the head, however, the dogs of the village having caused the complete disappearance of the rest of the bones.

As far as Ayres was able to ascertain the serpent was about 80 feet long. Its skin was a brownish black and resembled that of an eel. A spiny dorsal fin, as in an eel, ran down the back.

The head when taken from the pole was in a putrid condition and Ayres has cured it somewhat crudely, chunks of dried flesh still adhering to the jaws.

Ayres contends that the inevitable dragon pictured on Chinese flags is nothing more or less than the sea snake and claims that the latter is a direct descendant of the mighty plesiosaur which roamed the seas during prehistoric times.

The head will be sent to Baron Rothschild in England, negotiations for its purchase being at present under way.

When Ayres returns he will endeavor to locate the missing bones of the reptile and intends to circulate a notice among the native fishermen, offering a handsome reward for a sea serpent in the flesh preferably alive” (“Marine snake head from China”, 1905).

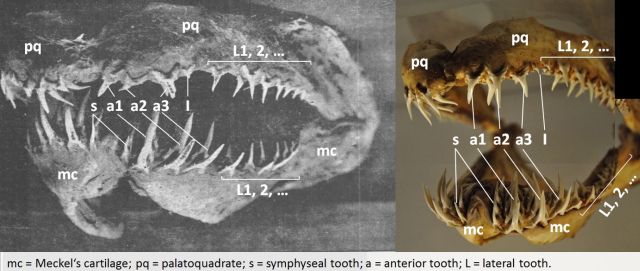

The identification as shark or more specific as sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus) of the family Odontaspididae can be deduced from the accompanying photograph of the article. Subsequent anatomical description and terminology is derived from Applegate (1965), Hamlet (1999), Iuliis & Pulerà (2007), Klimley (2013) and Purdy (1996) and is visualized in Fig. 3 and 4.

Photographic evidence

Fig. 3. Jaw of the sea serpent and C. taurus in correct position with added anatomical terminology used in text. (From “Marine snake head from China”, 1905. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Used according to § 51 Urheberrechtsgesetz; Merryjack. 2012. Grey nurse shark lower and upper jaw. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/merryjack/8220600560/ and https://www.flickr.com/photos/merryjack/8219517843/. Used under license CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0).

The photo shows no complete head as stated from the newspaper, only the mandibular arch is presented. The arch is formed from the palatoquadrate (upper jaw) and Meckel’s cartilage (lower jaw), each consisting of two fused halves. The palatoquadrate in C. taurus is longer than Meckel’s cartilage, sloping downwards and causing an overbite; additionally the presence and position of symphyseal and intermediate tooth’s reveal that the arch was photographed in inverted position. Therefore the mandibular arch was photographed from the anterior end and slightly from the lateral left side.

Fig. 4. Tooth of C. taurus with added anatomical terminology used in text. (From Merryjack. 2012. Grey nurse shark lower jaw. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/merryjack/8220600560/. Used under license CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0).

About 40 usually long and slender, triangular and inwardly curved pointed teeth – in two or more rows behind another – are visible and allow species determination. Each tooth is formed from an arch-shaped root followed from the crown. Left and right the central cusp of the crown are tiny lateral cusplets. Obviously some teeth in the different rows are missing. The given basic dental position for C. taurus is for the upper jaw three anterior, one intermediate, seven lateral tooth and for the lower jaw one symphyseal, three anterior, eight lateral tooth.

Comparisons of those features and known distributions off China show that the “head” of the sea serpent dragon actually is from a sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Markus Bühler for a second opinion on the assumed identification, to Dr Karl Shuker who brought this case to my attention with his book and to Yvette Noelani Kama, who shared her knowledge about the local newspaper-article (even as I already had found it before reading her comment).

References

Applegate, Shelton P. (1965). Tooth terminology and variation in sharks with special reference to the sand shark, Carcharias Taurus Rafinesque. Los Angeles County Museum Contributions in Science, No. 086.

Campagno, L., Dando, M. & Fowler, S. (2005). Sharks of the world. News Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

Hamlett, William C. ed. (1999). Sharks, Skates, and Rays: the Biology of Elasmobranch fishes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Iuliis, G. & Pulerà, D. (2007). The Dissection of Vertebrates: a laboratory manual. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Klimley, A. (2013). The Biology of Sharks and Rays. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Marine snake head from China. (1905, February 16). The Pacific Commercial Advertiser.

Model of China’s dragon. (1905a, May 5). Ellis County News.

Model of China’s dragon. (1905b, May 5). Quenemo News.

Model of China’s dragon. (1905c, May 11). The Beloit Daily Call.

Model of China’s dragon. (1905d, May 12). The Shawnee County News.

Model of China’s dragon. (1905e, May 17). The Citizen Wed.

Model of China’s dragon. (1905f, May 25). The Americus Greeting.

Model for China’s dragon. (1905, June 22). El Paso Morning Times.

Model of China’s dragon. (1906, June 7). Plainville Gazette.

Muirhead’s mysteries: A sea serpent head in Honolulu. (December 10, 2014). Retrieved from http://www.forteanzoology.blogspot.com/2014/12/muirheads-mysteries-sea-serpent-head-in.html

Purdy, Robert W. (1996). A Key to the Common Genera of Neogene Shark Teeth. Retrieved from http://www.nmnh.si.edu/paleo/shark.html.

Shuker, Karl. (2016). Still in search of prehistoric survivors: the creatures that time forgot? Greenville, Ohio, USA: Coachwhip Publications.